Here we present an account of Edith Cavell’s life, death and lasting significance. The text is from a booklet published for Swardeston Church back in the late 1990s compiled and written by the then vicar, Rev Phillip Mcfadyen. The booklet is still available in church.

Childhood

The Reverend Frederick Cavell came to Swardeston soon after he was ordained. He evidently knew what he was taking on as he had spent some years as the curate of neighbouring East Carleton. He liked Swardeston so much that he remained there for the rest of his ministry some 46 years. Frederick Cavell was trained for the ministry at Kings College, London and his certificate is to be found hanging at the back of Swardeston Church. While he was training in London, he fell in love with his housekeeper’s daughter but they were not to be married until she had completed some extra education and thought fitted to the role of a parson’s wife. In 1863, after twelve years at East Carleton, Frederick Cavell accepted the living at Swardeston. Two years later, Edith Louisa Cavell was born, on December 4th, 1865.

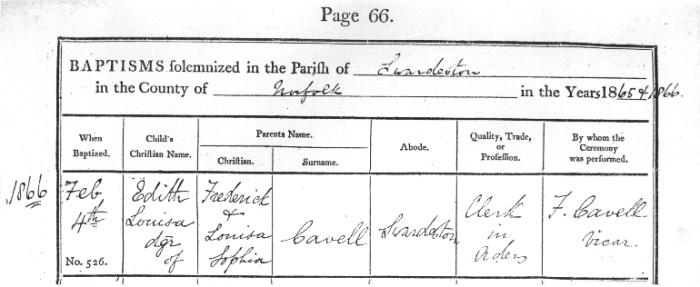

Edith Cavell’s entry in the Baptism register of Swardeston Church.

Edith Cavell’s entry in the Baptism register of Swardeston Church.

At first the Cavells lived in a temporary parsonage some distance from the Church at the bottom of Swardeston’s beautiful common.

Cavell House, Edith Cavell’s birthplace

Cavell House, Edith Cavell’s birthplace

This fine Georgian farmhouse is still standing and is known as ‘Cavell House’ as it was here that Edith was born in 1865. In that same year, a new Vicarage was built next to the Church.

The Cavell’s Vicarage in Swardeston, now a private house

The Cavell’s Vicarage in Swardeston, now a private house

This was the house in which Edith grew up and knew as her home. It was here that the three younger children, Florence, Lilian and John, were born. The Vicarage was built at Frederick Cavell’s own expense and local people say that it nearly ruined him. He was always a ‘poor parson’ from that time. Although the family lived frugally, they had to employ staff to help run such a large house and keep up appearances. The staff were evidently paid a subsistence wage as scratched on an attic bedroom wall are these words pencilled by a maid in 1876: “The pay is small, The food is bad, I wonder why I don’t go mad.” Obviously an intelligent and discerning maid, as most girls in service would not be so literate. Even if the family were poor and the food not very appetising, they were concerned to share what they had with their poorer parishioners. Sunday lunch was a great family affair and whatever was cut from the Sunday joint, an equal amount was taken out to hungry cottagers nearby.

The Interior of Swardeston Church before c.1900

The Interior of Swardeston Church before c.1900

Sundays in a Victorian Vicarage could be gloomy by today’s standards. No cards, no books allowed except the Bible. Frederick Cavell was something of a Puritan and would want to keep a strict Sabbath. Edith wrote to her favourite cousin Eddie, “Do come and stay again soon, but not for a weekend. Father’s sermons are so long and dull”. It is said that the Cavell children did occasionally sneak a game of cards in the study when Father was in Church. They certainly were not dour and sour Victorians that many biographies suggest. The Vicar could easily be tempted to disguise himself as a bear and cause the Cavell children to shriek with delight.

Pastimes

A chalk drawing by Edith Cavell

A chalk drawing by Edith Cavell

One of Edith’s favourite winter pastimes was ice skating. A 96 year-old member of the Unthank family who lived at Intwood Hall can recall seeing her skating down by the ford at Intwood and obviously enjoying herself. Nearer at home, the moat at the Old Rectory behind the Church would often freeze in winter and this was a favourite haunt of the Cavell children. Spring in Swardeston is still a spectacle of wild flowers around the common, although many species are disappearing (there were some 200 in her day). Edith had a great respect and love of nature and she seems always to have surrounded herself with plants and animals. Many of her photographs show her with her dogs and the Church has two chalk drawings of reindeer dated 10.10.82, showing the influence of the favourite Victorian painter, Landseer. Flowers were a fascination to her and she would collect and draw them as they grew on the common. She soon became a very accomplished artist and one or two village folk treasure examples of her work. A powder box given to Mrs. Emma Burgess at the birth of her baby was beautifully painted with flowers by Edith.

Grand Schemes

When Edith was a girl, she was aware that her father badly needed a Church room to house the growing Sunday School for the children of the village. She determined to do something about it. She wrote to the Bishop of Norwich, John Thomas Pelham, a grand but kindly man whose impressive tomb can be seen in the North transept of the Cathedral. She told him of the problem and he agreed to help, provided the village would raise some of the cash. Within a short time, Edith and her sister were making good use of their artistic talents and had painted cards which they sold to help raise some £300 for the Church room. Edith wrote to the Bishop reminding him of his promise and so the Church room was built adjoining the Vicarage and to all accounts, very well used. Both Mrs. Cavell and Edith taught in the Sunday School and acted as godmothers to a number of local babies, who in later years still treasure their signed copies of the Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress. [Sadly, this Church room was sold by the diocese at the time of the sale of the Vicarage and the parish was again without its Church room. However, in recent years, a new Church room has been provided in the Churchyard adjacent to the North door of the Church, of an imaginative wooden design, and is known as the ‘Cavell Room’ in honour of Edith, who worked so hard for the village and its children.]

The East window in Swardeston Church is a memorial to Edith. The Church always has a fine show of flowers and the Cavell Festival weekend nearest to the date of her execution (12th October) has become a biennial Flower Festival, when the village gives thanks for Edith’s memory and invite people to share in her appreciation of God’s creation.

Children enjoying a summer’s day, probably on Swardeston Common.

Children enjoying a summer’s day, probably on Swardeston Common.

From a drawing by Edith Cavell, courtesy of Swardeston Church.

Edith could never have known she was to become a heroine and martyr but she is said to have confided in a lighthearted way to a friend that she would like to be buried in Westminster Abbey. The first part of her impressive funeral took place there, attended by Queen Alexandra, Princess Victoria and many others from all walks of life with military and nursing representatives from many parts of the world. By popular demand, her body was brought back to her native Norfolk and lies at Life’s Green in the Cathedral Close. The grave is well tended and nearly always covered in flowers. Among Edith’s most treasured possessions were the roses sent by her nurses, which she kept in her cell long after they were spent, as a comfort and a reminder of the roses at the Vicarage in Swardeston.

Schooling and First Jobs

Edith and her two younger sisters, Florence and Lilian, had their early education not at the recently opened village school but at home. Later in 1881, Edith is thought to have spent a few months at Norwich High School, when it was housed at the Assembly House in Theatre Street, Norwich. She would have walked there, dropping off her brother ‘Jack’ (eight years old), at Miss Brewer’s school in Lime Tree Road. From sixteen to nineteen years old, Edith went to three boarding schools; Kensington (possibly St. Margaret’s, Bushey – a school for poor clergy families), Clevedon, near Bristol, where she was confirmed (15th March 1884) and finally Laurel Court, Peterborough, in the Cathedral precincts where she learnt to become a pupil teacher.

There were many such establishments at this time, unashamedly providing what was boasted as ‘a high moral training.’ Laurel Court was fairly typical, ruled by a ‘fearsome dragon’ and the place smelt of ‘cats, margarine and treacle’ (according to one ex-pupil). However, French was well taught here, with ten minutes conversation as part of the daily curriculum. Edith showed a flair for it and as a result was recommended for a post in Brussels in 1890. Prior to this, she took several jobs as a governess. Her first job was to look after a clergy household in Steeple Bumpstead. Despite the demands of her job, she still found time to keep up her hobbies of tennis and dancing. She once danced till her feet bled, which ruined her new shoes but cured her chilblains! She is remembered as being full of fun, always smiling and wonderfully kind to the children in her charge.

She was, for a short time, governess to some of the Gurney children at Keswick New Hall in the next village and was affectionately remembered. At about this time, Edith was left a small legacy and decided to spend it on a Continental holiday. She spent some weeks in Austria and Bavaria, and was deeply impressed with a free hospital run by a Dr. Wolfenberg. She endowed the hospital with some of her legacy and returned with a growing interest in nursing.

Brussels

In 1890, Edith took a post with the Francois family in Brussels. She stayed here for five years and became a firm favourite with the family, even though she objected to their jokes about Queen Victoria being a prude. She continued to paint in her spare time and became fluent in French.

Her summer breaks were spent in Swardeston, playing tennis and painting. A romantic attachment with her second cousin Eddie emerged at this time. Edith might have accepted him had he proposed but he confided to another cousin that he felt that due to an inherited nervous condition, he perhaps ought not to marry. They appear to have been in love and Edith never forgot him, for she wrote on the fly leaf of her copy of The Imitation of Christ ‘With love to E.D. Cavell’ on the day of her execution.

Nurse Training

1895 saw Edith’s return to Swardeston to nurse her father through a brief illness. He remained Vicar until his retirement in 1909. Helping to restore her father to health made Edith resolve to take up nursing as a career. After testing her vocation for a few months at the Fountains Fever Hospital, Tooting, Edith (Aged 30) was accepted for training at the London Hospital under Eva Lückes in April 1896.

In the summer of 1897, an epidemic of typhoid fever broke out in Maidstone. Six of Miss Lückes Nurses were seconded to help, including Edith. Of 1700 who contracted the disease, only 132 died. Edith received the Maidstone Medal for her work here – the only medal she was ever to receive from her country. Edith did not impress the redoubtable Miss Lückes, who was to say of her that “Edith Louisa Cavell had plenty of capacity for her work, when she chose to exert herself ” and that “She was not at all punctual”. By today’s standards, the hours were demanding (7 a.m. – 9 p.m., with half an hour for lunch) and the pay miserly (£10 a year). ‘The work is hard The pay is bad’.

Edith was recommended for private nursing in 1898 and dealt with cases of pleurisy, pneumonia, typhoid and a Bishop’s appendicitis. She soon moved back into the front line of nursing and in 1899 was a Night Superintendent at St. Pancras, a Poor Law Institution for destitutes where about one person in four would die of a chronic condition. At Shoreditch Infirmary, where she became Assistant Matron in 1903, she pioneered follow up work by visiting patients after their discharge. Those early pastoral visits with her mother in Swardeston obviously had a lasting effect.

In September 1906, Edith went to work for the Manchester and Salford Sick Poor and Private Nursing Institution as a nurse at one of the Queen’s District Nursing Homes, in a temporary position for three months. However, since the Matron, Miss Hall, became ill, she filled in as Matron. In a letter dated 12th March 1907, she wrote to Miss Lückes at London Hospital, saying that it was a heavy responsibility, and she knew little of the work of the Queen’s District Nurses. She asked if there were any trained nurses willing to fill in a three months post for pay of £30 per annum. Edith’s work in Manchester was commemorated by a splendid brass plaque, which was found in a Manchester scrapyard in April 2002.

Back to Brussels

Edith Cavell with some of her nurses in Brussels.

Edith Cavell with some of her nurses in Brussels.

In 1907, after a short break, Edith returned to Brussels to nurse a child patient of Dr. Antoine Depage but he soon transferred her to more important work. Dr. Depage wanted to pioneer the training of nurses in Belgium along the lines of Florence Nightingale. Until now, nuns had been responsible for the care of the sick and, however kind and well intentioned, they had no training for the work. Edith Cavell, now in her early forties, was put in charge of a pioneer training school for lay nurses, ‘L’Ecole Belge d’Infirmieres Diplomees’, on the outskirts of Brussels. It was formed out of four adjoining houses and opened on October 10th, 1907.

Edith rose to the responsibility immediately; despite her own early record of unpunctuality, she kept a watch before her at breakfast and any unfortunate woman more than two minutes late would forfeit two hours of her spare time. The work was quickly established, despite some resistance from the middle classes. Edith writes home …. “The old idea that it is a disgrace for women to work is still held in Belgium and women of good birth and education still think they lose caste by earning their own living.” However, when the Queen of the Belgians broke her arm and sent to the school for a trained nurse, suddenly the status of the school was assured. By 1912, Edith was providing nurses for three hospitals, 24 communal schools and 13 kindergartens. In 1914 she was giving four lectures a week to doctors and nurses alike, and finding time to care for a friend’s daughter who was a morphia addict, and a runaway girl, as well as her two dogs, Don and Jack.

War Declared

Edith often returned to Norfolk to visit her mother, who since her husband’s death was living at College Road, Norwich. They also had holidays together on the North Norfolk coast. She was weeding her mother’s garden when she heard the news of the German invasion of Belgium. She would not be persuaded to stay in England. “At a time like this”, she said, “I am more needed than ever”.

Edith Cavell with Dr Depage and the nursing staff at the Clinique.

Edith Cavell with Dr Depage and the nursing staff at the Clinique.

By August 3rd 1914, she was back in Brussels despatching the Dutch and German nurses home and impressing on the others that their first duty was to care for the wounded irrespective of nationality. The clinic became a Red Cross Hospital, German soldiers receiving the same attention as Belgian. When Brussels fell, the Germans commandeered the Royal Palace for their own wounded and 60 English nurses were sent home. Edith Cavell and her chief assistant, Miss Wilkins remained.

The initial German advance was successful and the British retreated from Mons and the French were driven back, many in both armies being cut off. In the Autumn of 1914, two stranded British soldiers found their way to Nurse Cavell’s training school and were sheltered for two weeks. Others followed, all of them spirited away to neutral territory in Holland. One from the 1st Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment recognised a print of Norwich Cathedral on the wall of her office; she was always delighted to receive someone from her beloved Norfolk, asking a private Arthur Wood to take home her Bible and a letter for her Mother. Quickly an ‘underground’ lifeline was established, masterminded by the Prince and Princess de Croy at a chateau at Mons. Guides were organised by Philippe Baucq, an architect, and some 200 allied soldiers helped to escape. (The password was ‘Yorc’ – Croy backwards). This organisation lasted for almost a year, despite the risks. All those involved knew they could be shot for harbouring allied soldiers.

Edith also faced a moral dilemma. As a ‘protected’ member of the Red Cross, she should have remained aloof. But like Dietrich Bonhoeffer in the next war, she was prepared to sacrifice her conscience for the sake of her fellow men. To her, the protection, the concealment and the smuggling away of hunted men was as humanitarian an act as the tending of the sick and wounded. Edith was prepared to face what she understood to be the just consequences. By August 1915 a Belgian ‘collaborator’ had passed through Edith’s hands. The school was searched while a soldier slipped out through the back garden, Nurse Cavell remained calm – no incriminating papers were ever found (her Diary she sewed up in a cushion). Edith was too thorough and she had even managed to keep her ‘underground’ activities from her nurses so as not to incriminate them.

Two members of the escape route team were arrested on July 31st, 1915. Five days later, Nurse Cavell was interned. During her interrogation she was told that the other prisoners had confessed. In her naivete she believed them and revealed everything. Many people think that Edith ‘shopped’ her compatriots simply because, like George Washington, she could ‘never tell a lie’. This was far too simplistic an explanation. Edith was willing to abuse her position in the Red Cross to help her fellow countrymen in need. She would have equally protected her colleagues at the risk of compromising her own conscience even though this would have been painful and contrary to her upbringing. She was trained to protect life, even at the risk of her own. “Had I not helped”, she said, “they would have been shot”. The explanation is that Edith simply trusted her captors, was glad to make a clean breast of it and willingly condemned herself by freely admitting at her trial that she had “successfully conducted allied soldiers to the enemy of the German people”. Herein lay her ‘guilt’, and this was a capital offence under the German penal code. She was guilty, so they must shoot her.

Last Days

The German military authorities, having sentenced Edith and four others to death, were determined to carry out the executions immediately. Despite the intervention of neutral American and Spanish embassies, Miss Cavell and Baucq were ordered to be shot the next day, October 12th, at the National Rifle Range (The Tir Nationale). A German Lutheran prison chaplain obtained permission for the English Chaplain, Stirling Gahan, to visit her on the night before she died. For his account, click here. His account of her last hours is very moving. They repeated the words of ‘Abide with me’, and Edith received the Sacrament.

She said, “I am thankful to have had these ten weeks of quiet to get ready. Now I have had them and have been kindly treated here. I expected my sentence and I believe it was just. Standing as I do in view of God and Eternity, I realise that patriotism is not enough, I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone”.

Stirling Gahan’s Communion set, used on the day he visited Edith Cavell.

Stirling Gahan’s Communion set, used on the day he visited Edith Cavell.

Photo by kind permission of Martin Gahan, Stirling Gahan’s grandson.

Edith was magnanimous in her death, forgiving her executioners, even willing to admit the justice of their sentence. This sentence was carried out hurriedly and furtively in the early hours of October 12th. Two firing squads, each of eight men, fired at their victims from six paces. Stories were told that the men fired wide of Edith, that she fainted and was finally despatched by a German officer with a pistol. Reliable witnesses report nothing of this and it seems the executions were carried out without incident. For an eye-witness account of the executions, by the prison Chaplain, please click here. However there has recently come to light a collection of press cuttings dating from 1919 to 1974 compiled by a J.F. Randerson of Canterbury. This devotee of Edith’s memory records what he calls a ‘strange confirmation’ of Arthur Mee’s story that one of the firing squad refused to take part in the execution. Private Rimmel is said to have thrown down his rifle when ordered to fire at Nurse Cavell and to have been shot by a German officer for refusing to obey orders. A near neighbour of Randerson testified to being present at a secret exhumation of a German soldier who had been hastily buried near the grave of Edith. There may be some truth in the story that the firing squad were reticent and that one of them may have been shot with the brave British nurse.

Returning Home

The outcry that followed must have astounded the Germans and made them realise they had committed a serious blunder. The execution was used as propaganda by the allies, who acclaimed Nurse Cavell as a martyr and those responsible for her execution as murdering monsters. Sad to think that this was contrary to her last wishes. She did not want to be remembered as a martyr or a heroine but simply as “a nurse who tried to do her duty”. The shooting of this brave nurse was not forgotten or forgiven and was used to sway neutral opinion against Germany and eventually helped to bring the U.S.A. into the war. Propaganda about her death caused recruiting to double for eight weeks after her death was announced.

Edith Cavell’s Grave in the Tir Nationale.

Edith Cavell’s Grave in the Tir Nationale.

Edith had been hurriedly buried at the rifle range where she was shot and a plain wooden cross put over her grave. The shaft of this cross can be seen preserved at the back of Swardeston Church. When the war was over, arrangements were made for Edith’s reburial.

At first, Westminster Abbey was considered but the family preferred Norfolk. Her remains were escorted with great ceremony to Dover and from there to Westminster Abbey for the first part of the burial service on May 15th, 1919.

Awaiting Edith Cavell’s Coffin, Victoria Station, London.

Awaiting Edith Cavell’s Coffin, Victoria Station, London.

Photo courtesy of Sue Rickards, whose Grandfather is the soldier on the left.

Return to Norfolk

A special train took the remains to Norwich Thorpe Station and from there, a great procession to the Cathedral.

The Scene at Thorpe Railway Station, Norwich.

The Scene at Thorpe Railway Station, Norwich.

Bishop Pollock described her as ‘alive in God’ and as someone who taught us that our patriotism must be examined in the light of something higher. She was laid to rest outside the Cathedral in a spot called Life’s Green. Here services are held annually on the Saturday nearest the anniversary of her death.

Edith Cavell’s coffin arrives at Norwich Cathedral for burial.

Edith Cavell’s coffin arrives at Norwich Cathedral for burial.

Carried to her final resting place at Life’s Green by the East end of Norwich Cathedral.

Carried to her final resting place at Life’s Green by the East end of Norwich Cathedral.

A Final Word

Edith Cavell’s character continues to fascinate today. Mount Edith Cavell in the Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada is a tribute to her. For photographs of a memorial service to Edith Cavell, held on the slopes of the Mountain in 1931 click here. Anna Neagle made a film of her and Joan Plowright appeared in a a very successful play called ‘Cavell’. Sadly there was a time when her name was associated with an extreme form of patriotism, despite her words that this is ‘not enough’. As a result, some have shied from her memory. A truer assessment of her would be to recognise her as she saw herself – simply ‘a nurse who tried to do her duty’. Her perception of duty challenges us today; in achieving the greater good (or the lesser evil), we may compromise our reputation and even endanger our good name. Edith, in doing what she considered her duty, was prepared to go further and surrender her life and liberty to relieve suffering and help others achieve freedom.

In the light of recent releases of British Secret Service files from the Great War period, we have a better idea of how much Edith knew of the personal danger she faced in carrying on with helping soldiers to escape. From this we can see that she was not as naïve as some commentators would have us believe. She was a very brave woman, driven by a sense of duty, of patriotism, and by the practical living out of her personal faith in the Lord Jesus Christ. She would have wanted all the glory to go to Him.

Text written by Revd Phillip McFadyen, Vicar of Swardeston in 1985

and added to by his successor Revd David Chamberlin thereafter.

Quotation is permitted provided acknowledgement is made of the source.

Copyright © 2015 Parochial Church Council of St Mary’s Church Swardeston

Norwich Norfolk NR14 8EB

Edith’s Legacy

In 1917 funds raised by two national newspapers in memory of Edith Cavell were dedicated to the creation of at least six rest homes for nurses around England. The Cavell family had suggested this on the grounds that she had said that when she came to retirement she would hope to provide this care. Many nurses had suffered in the War and needed ‘time out’ or long term care.

Today this work on behalf of nurses is still going on under the Cavell Nurses Trust. See their website for details – www.cavellnursestrust.org